On my journey to become a funeral director, I spent two hours a day, five days a week, commuting from my hometown of Dayton, Ohio to attend the Cincinnati College of Mortuary Science. Each day as I made the long drive down I-75 to learn about death and dying, I traveled parallel to Interstate 71. That highway upon which transgender teen, Leelah Alcorn, ended her own life by walking in front of an oncoming truck, seeing it as a preferable experience to being trans in America[1]. In a final, timed social media post she pleaded with us, her readers, to “Fix society. Please.”

Her parents made funeral arrangements for her under a name and identity with which she found so unbearable that she chose death instead—one final indignity she was made to suffer. On more than one misty morning drive I found my mind wandering down that parallel path. What if I had been there instead of that truck, making my way to Cincinnati to learn about how to protect Leelah’s legacy? Could I have stopped her, gotten her to safety, ensured she had the love and care that she so desperately needed? No amount of magical thinking can bring her back, and though I know it will take more than one person to fix this abattoir of a society we live in, I know that I must still try. Because “rest in peace” shouldn’t be a luxury only afforded to bodies and lives that conform to our ever-reductive societal norms.

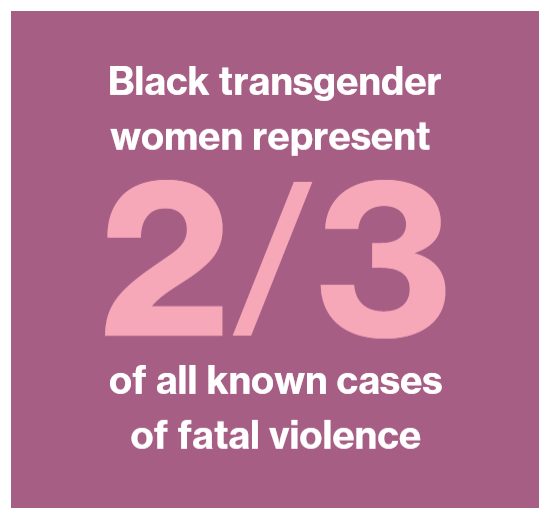

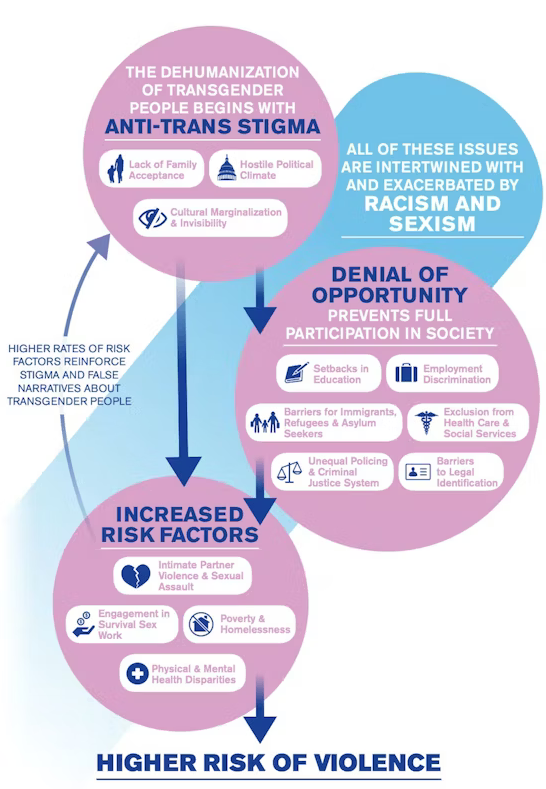

Death is the great equalizer—we hear that all the time, right? Everyone eventually dies—rich, poor, black, white, gay, straight, bi, pan, cis, trans—everyone. But I know all too well that the circumstances around death, and the death system here in America, are anything but impartial. For instance, LGBTQ teens are four times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers[2]. The Trevor Project reported in 2022 that forty-five percent of LGBTQ youth seriously considered suicide in the previous year, including more than half of transgender and non-binary youth. Furthermore, since the FBI started tracking hate crimes against Trans and Gender Non-Conforming people in 2013, three hundred and two deaths by violence have been documented, the victims being overwhelmingly people of color under thirty-five years old[3]. And these are just the ones we know about.

There have been numerous studies showing that trans and gender non-conforming communities and individuals experience significantly higher levels of violence, not only from strangers, but also family, police, and even partners. They also experience increased rates of poverty and exposure to employment or housing discrimination[4][5]. All contributing factors to experiences of mental illness and substance abuse, which are then exacerbated by limitations in access to healthcare and often, even further discrimination.

All of this before you even reach the funeral home, which presents its own set of problems.

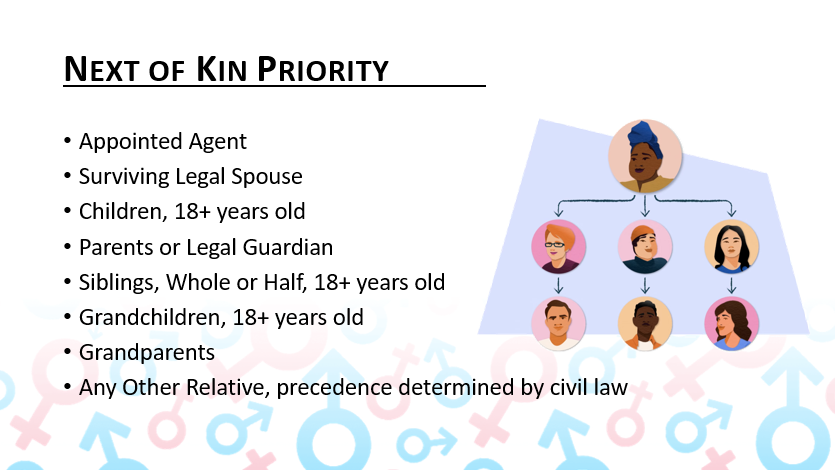

When people come into our care, funeral directors are tasked with collecting some very personal information about them. Birth date and location, parents’ names, marital status, race, ethnicity, death date and location… and gender. This is one of our duties that is necessary for things like filing death certificates and getting burial or cremation permits. Most of this information comes from legal documents, such as social security cards and driver’s licenses—or next of kin—whether a spouse, an adult child, a parent, or sibling. But whomever it is, we must rely on the information they give us, even if the person we’re caring for might be presenting as a gender different than what the family is telling us.

The frustrating reality of our position is that in these cases, the legal next of kin is often family which that person has been estranged from. If we have no legal documents showing otherwise, they can tell us whatever they want in terms of the name and pronouns of the deceased. They can bring us whatever clothing they want that person to be put in for a viewing. They can instruct us to shave their facial hair or crop their ponytail. They can select whatever photo they want for the obituary. They can choose to hold private services, restricting romantic partners, friends, and chosen family from attending their loved one’s funeral—a vital part of the grieving process.

If someone doesn’t tell us, there is not typically another way for us to know the true name this person used, or their true pronouns. Perhaps they were socially transitioning without their family’s knowledge. Did they know and didn’t approve, and now suddenly this unsupportive family is overseeing their legal documentation? Is this photograph of them I’ve been given for the obituary accurate to how they wanted to be seen in life? Even if I do know there is a discrepancy, I can’t force a publication to change the name they’re using for someone if the legal next of kin ordered them to use specific information. Infuriatingly, there is nothing we can do when this happens, except outright refuse service. There is a name for what they’re doing—misrepresenting these people—it’s called “nonconsensual detransitioning” and though it is grossly unethical, it isn’t illegal.

There is a name for what they’re doing—misrepresenting these people—it’s called “nonconsensual detransitioning” and though it is grossly unethical, it isn’t illegal.

The good news is that in every single state, you can appoint an agent to oversee your funeral decisions who takes precedence over all those unsupportive family members. The most important thing you can do is to decide who you want to oversee all these decisions and put that in writing. At the very back of the preplanning information packet I created, that can be found here, is a form you can fill out in mere minutes, designating someone to make decisions about your funeral. It supersedes any legal next of kin. This is something I advise everyone to do, even if there is no hint of conflict or uncertainty in your family. It simply helps expedite the funeral arrangement process for everyone by making clear who is in charge.

The Appointment of Representative for Bodily Disposition and Funeral Decisions, i.e., an “Agent Form”, is a simple form that either needs to be notarized or signed by two witnesses and given to your funeral director to be binding. Notary services can typically be found at your bank, many Motor Vehicle offices, and even the UPS Store. If using witness signatures, please remember that you cannot witness your own signature, it must be two people other than yourself and the person you are nominating. Though the form included in my preplanning packet is specifically for Ohio, every state has a similar form or procedure, which can be accessed by visiting Funerals.org.

This packet also includes a checklist of further end-of-life planning essentials. Things like nominating a healthcare power of attorney, and making an advanced directive or living will, which empowers someone trusted to advocate for you when you cannot. If you are ever in a position where you are too sick or incapacitated to speak for yourself regarding medical decisions, this puts someone in charge who knows your wishes. In most states, a healthcare proxy cannot be overridden by next-of-kin, even if they disagree with whatever decisions are being made. But be aware that power of attorney ends at death, so naming a Representative for your funeral decisions is still necessary. Creating a living trust will also help your advocate by automatically conferring your estate to them upon death, giving them immediate access to vehicles, property, and other assets, which they may need to help plan or pay for final expenses. By skipping the long process of probate court, which takes an average of nine months in Ohio[6], you can ensure everything they need is at their fingertips.

When filling out these forms, ensure that you speak with the person who you’re nominating! Have these tough conversations, let them know what you would like to happen at the end of your life and for your funeral, with your bodily remains after the funeral, and why you are entrusting them with such an important task. Get talking about funeral details that are important to you, such as what type of service you would like to have, a special song you want played, what you would like to be done with your bodily remains, and more.

Do you want a traditional burial in a cemetery with a visitation the night before and a service in the morning, or would you rather be cremated and have an informal celebration of life held after the fact? Do you want to be embalmed—that’s a very personal decision and contrary to popular belief, not required by law. Perhaps you would like a natural burial with an ecofriendly basket casket, or even just a simple shroud? Maybe you’d like something more extravagant, like having your cremated remains launched into space—it’s possible! Or maybe, just maybe, you have considered anatomical donation to help mortuary students learn how to give compassionate care to the dead. No matter what you choose, the ability to customize your final wishes should be in your hands.

Once you start talking, let other people know! Tell your friends, your doctor, your partner, your lawyer, your neighbors—tell everybody! A lot of people will balk at the idea of having these conversations because they can be difficult. But they are so worth having. When trans identities are erased by misinformation and disinformation perpetuated by hostile legal systems, adversarial media, hateful religious institutions, and demeaning family members, their very humanity is being denied. We are living in a time where trans and gender non-conforming bodies and lives are being continually put up for debate and targeted for not only personal, but institutionalized violence. So, the rest of us had better stand up and start showing some basic fucking human decency. Together we can protect the myriads of beautiful identities that you all have fought so very hard for—a death without deadnames.