“The main work of haunting is done by the living.”

—Judith Richardson

Spooky Season, Shocktober, Gay Christmas— call it what you will, Halloween has become a most sacred holiday to those of us that fall outside of the “norm” and it seems especially dear to the LGBTQIA+ community. We treasure our ghoulish icons like Elivra, Mistress of the Dark—especially since she came out in her recent memoir! We revel in the kooky camp of gaudy Halloween store decor and go wild creating over-the-top costumes and gags. We eagerly gorge ourselves on queer horror films and television shows that range from black and white lesbian-coded classics like The Uninvited and Rebecca, to modern gay ghost-hunting shows like Queer Ghost Hunters and Living for the Dead. Halloween is a time when we can unapologetically let our freak flag fly, dress however we want, camp it up, enjoy a good scare, and indulge in all the delightful debauchery that the holiday has to offer. But underneath all the smiling plastic jack-o’-lanterns and sickeningly sweet treats lurks a deeper connection to the haints and haunts of Halloween that reaches a spectral hand right into our little queer hearts.

What is it about ghosts and ghost stories that resonates so deeply with the queer community? Is their wispy, translucent nature, a reflection on our legacy of forced societal apparitionality? Are we enamored by their ability to torment those who have wronged them, wishing that we too could bring a reckoning down upon our oppressors? Artist Abby Neale of The Gay Ghost Manifesto poses that many of the elements which make up a good ghost story are also present in the reality of queer histories. “Ghost stories spread through campfires, sleepovers, and whispers. No editors or hierarchy determines a cannon or rules, it is an oral tradition. Queerness and queer counterculture also share this rhizomatic lack of a hierarchy. Without an organized hierarchy, queer people decide their stories and destinies parallel to a dominant straight, cis narrative. […] Pieces of queer and trans history often have been erased, we have no idea how figures like Joan of Arc, or women in Boston marriages might identify with our contemporary ideas. Blurring the lines between past and present plays a key role in any good ghost story.”

“These tours are so fun because gay history is not written down, and it’s all folklore. I’ll be on the tour and this old queen will interrupt with something that they heard when they came to New Orleans in the ‘70s, so these history tours become super communal.”

-Marcus Shacknow , Walking with the Gay Ghosts of New Orleans

Adding to these blurred lines is a foundational part of our American obsession with ghosts—the Spiritualist movement. In a small upstate New York home in 1848, the Fox Sisters, Kate and Margaret , created a cultural fascination with the idea that we could communicate directly with the dead. A DIY religion which empowered women and made the spirit world accessible to all, the American Spiritualist Movement created circles where women saw no need for the rigid patriarchal structures of organized religion and the men who enforced them. The movement became dominated by forward thinking women and inexorably entwined with women’s suffrage, with many seeing Spiritualism as an antidote to the misogyny of traditional religion. By allowing the dead to speak through them as mediums, Spiritualism gave many women practice and confidence in speaking to groups with authority, a vital factor of the social movements necessary to drive women’s suffrage. The second half of the nineteenth century saw the movement dwindle as it became associated with not just the rejection of patriarchal religion and traditional marriage, but women’s rights and other “subversive” agendas, in a particularly venomous, misogynist backlash. Though it may be defunct, deradicalized, and divorced from the social agenda it created, the Spiritualist movement laid the groundwork for how we think of—and how we interact with—the ghosts of our collective past and taught us how we can use those stories to empower our own marginalized identities.

Throughout history, societies have demonized and made monsters of anyone and everyone who was seen as “other.” People outside gender and sexual norms, people with different religious or cultural backgrounds, people with mental illnesses, left-handed people, people with physical impairments, scientists, suffragettes, pinkos—you name it. In Mary Shelly’s horror classic, Frankenstein, the monster is often referred to as “The Other”–the word implying that something is distinctly and drastically different than what is already known or established. Cultures align marginalized groups with villains or demons to equate them with the profane and make it clear to their constituents that these people are undesirable and not to be associated with. What a particular society finds monstrous typically expresses the fears of that society, and each society makes its monsters as a device to keep its people under control. Don’t stray from the path we’ve set for you, Little Red Riding Hood, or something unthinkable will happen. Using scare-tactics and not-so-subtle coding, oppressed people have been woven into the fabric of tall tales and spooky stories for as long as humans have been telling them. Is it any wonder that since we have been made into specters and shades, we have embraced the role?

When asked about the delightfully dark and sinister aesthetic infused into their television show Dragula, and their own personal brand, performers and all-around icons, the Boulet Brothers said “I think many gay men who grow up not fitting into the universal idea of masculinity and male beauty can relate to fictional, fabulous angry outsiders like Disney villanesses or (depending on your generation) people like Siouxsie Sioux, Lady Gaga, or characters from the Rocky Horror Picture Show. If you are kind of fem and creative looking, these are your heroes. They were dark and moody, but fabulous and iconic and powerful – everything a lot of gay guys at that age wants to be. These characters are not victimized for being outsiders but empowered by it, and so there is strength in that darkness that you can look up to. Life isn’t muscley and pretty and fish and rainbow flags for all gay men, and growing up can be painful. As you can imagine, pain comes with a little darkness.” Beyond just gay men, queer-coded villains and other spooky tales inspired many LGBTQ+ youth searching desperately for representation in our art and entertainment since so many tales of our collected queer ancestors have been lost to time, or worse yet—intentionally obscured or destroyed. After all, why shouldn’t we reclaim our queer monstrosity as we have done with so many other things, including the word itself.

“I see now how these spectral presences, by being seen and not seen, by exerting energy where none was anticipated, spoke to the queerness I felt within me and didn’t understand. At that time in my life, I experienced my queerness as an unknowable force, something that might well try to lure me out into the cold, something that I tried not to look at directly. […] Queerness was something to do with other people. And yet, like the ghosts in the stories I loved, there it was, an alluring and alarming possibility, which I could talk about with exactly no one, and which was both more precious and more terrifying for the silence that surrounded it.”

-Nell Stevens, What Ghost Stories Taught Me about my Queer Self

Recently, I attended an End-of-Life symposium and had the privilege of listening to an older gay man recount the story of how he became involved in palliative care. He spoke about coming of age in the 1980’s and becoming, in his early 20’s, a hospice nurse in all but name as the people he loved began dying of what was then known as Gay Related Immune Deficiency, or GRID. At the time, most hospitals and hospices refused to serve patients with the disease, leaving many to die in group homes hastily put together by their peers, as their families also refused to take them in upon learning of their sexual identity and diagnosis. Though it goes by a different name now, HIV/AIDS was and still very much is, a disease of silenced and forgotten bodies. HIV/AIDS has been sensationalized in Western culture as afflicting bodies it views as other—most typically, gay male bodies, promiscuous bodies, Black bodies, and intravenous drug-using bodies. All these bodies were used up by President Reagan and his “Moral Majority” to construct a plague that threatened the conservative body politic. The administration manipulated facts and access to information on an illness they could hold up as “proof” of the threat from these others to the body of the American family—justification for their genocide.

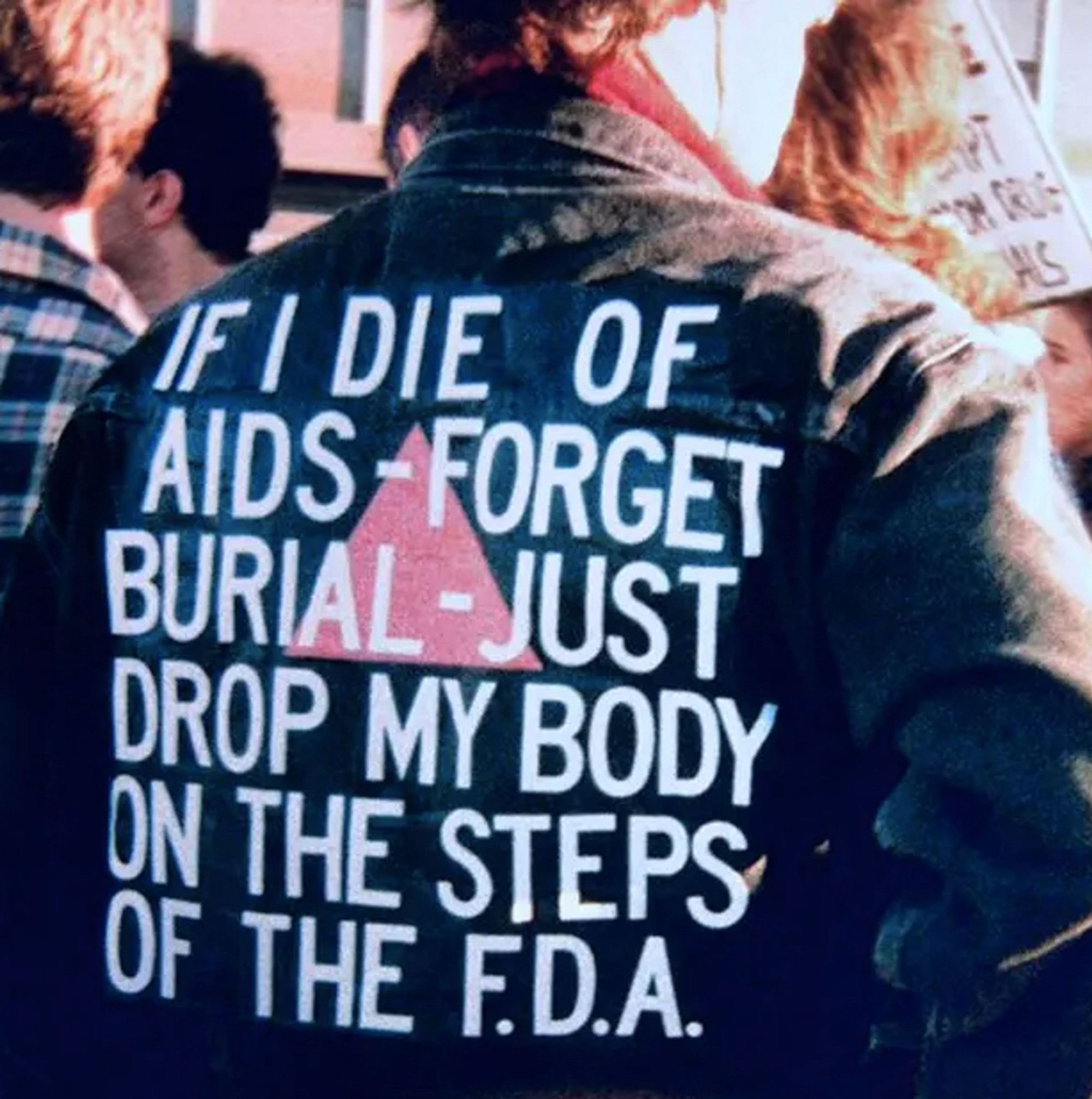

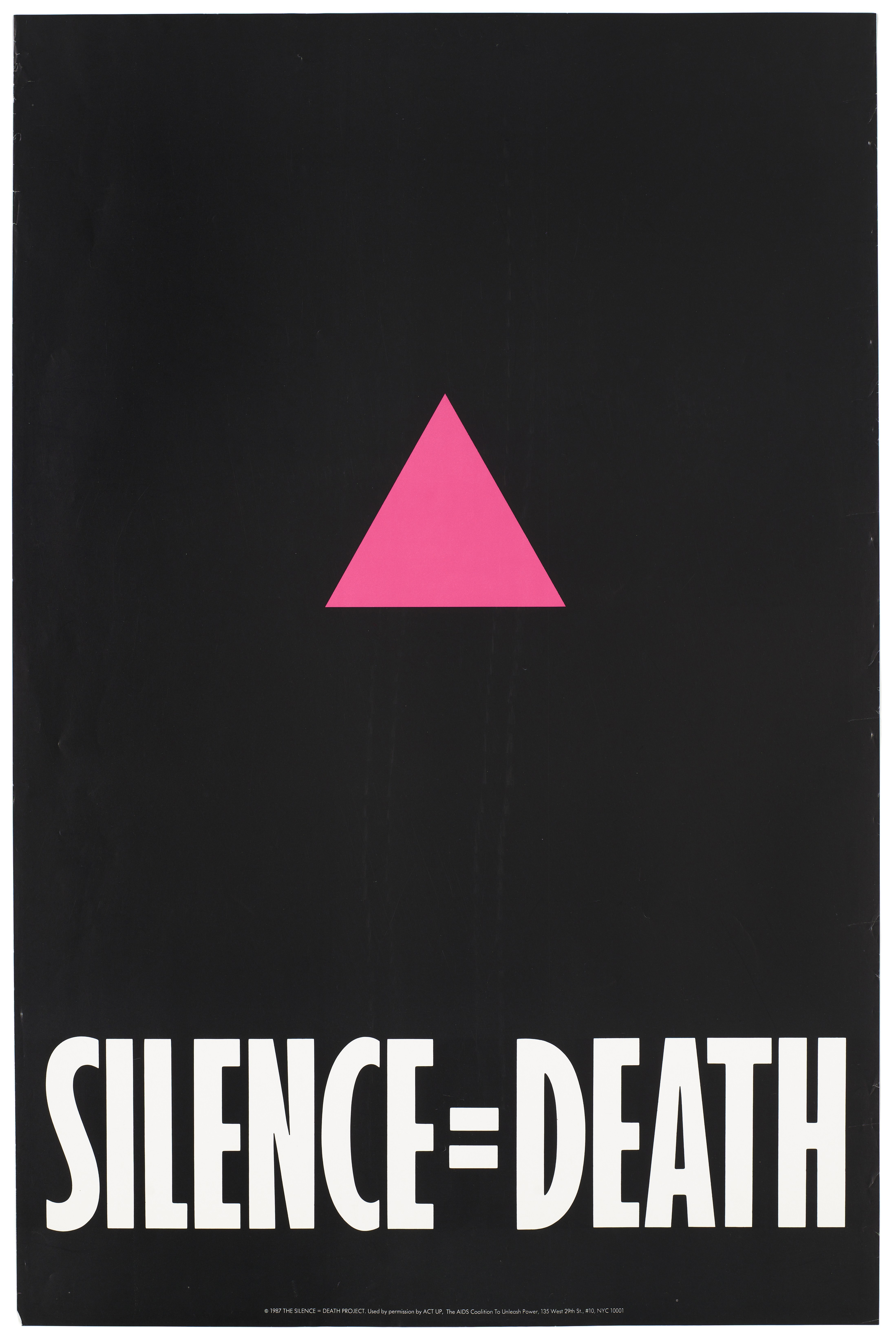

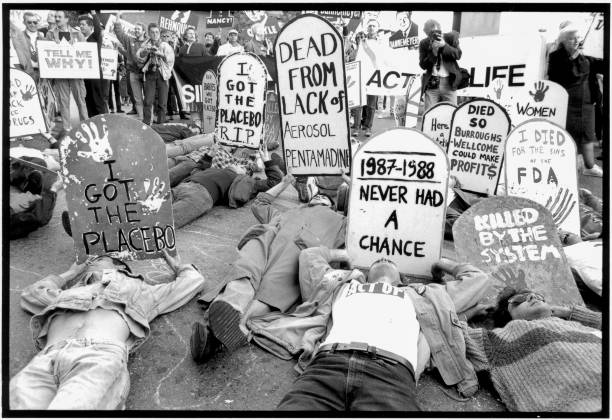

Many ghosts are left in the wake of HIV/AIDS—not just the people and bodies living with the disease, who in pop-culture were often portrayed as haunted, but others, like the ghosted female bodies with AIDS, or the sudden, haunting absence of so many young people from once vibrant urban communities. The survivors learned how to companion and care for their own dead and dying because the people who would have typically assumed those roles—like doctors, nurses, and morticians—simply refused. This created an entire generation of queer people who gained a collective cultural intimacy with death like none before. Building upon a history of activism which made bodies the focal point of protest, the ACT UP movement was formed during the sixth year of the epidemic after a rousing speech by playwright and LGBTQ activist Larry Kramer at the New York Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center in 1987 where he asked, “How long does it take before you get angry and fight back?” Realizing that the administration would never end its’ silence and refusal to act, protesters began a campaign of civil disobedience measures, including wheat-pasting the now iconic SILENCE=DEATH posters across New York City, staging die-ins, and conducting public funerals.

Activists feigned death in public spaces, often sporting cardboard tombstones with slogans like “DEAD FROM LACK OF DRUGS” and “VICTIM OF F.D.A. RED TAPE” to protest the delayed approval and restricted access to desperately necessary drug treatments. Other die-ins saw signs like “KILLED BY THE SYSTEM” and “C.D.C. is KILLING WOMEN, redefine AIDS!” In its first decade, ACT UP held thousands of demonstrations, forcing the public to confront death on the steps of the Food and Drug Administration, the Centers for Disease Control, Wallstreet, Grand Central Station, National Institutes of Health, the streets of San Francisco and Chicago—and even at the vacation home of then President, George H. W. Bush. Further protests saw coffins borne through the streets and cremated remains spread on the White House lawn. In an interview in 2002 with the New Yorker, Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health, said that “Before AIDS and before ACT UP, all experimental medical decisions were made by physicians. Larry Kramer, by assuring consumer input to the F.D.A., put us on the defensive at the N.I.H. He put Congress on the defensive over appropriations. ACT UP put medical treatment in the hands of the patients. And that is the way it ought to be.” These heart wrenching realities of queer death on display turned the tides of media attention, swayed public opinion, and inspired LGBTQIA+ and other marginalized communities across the globe to put confrontations with death at the center of their public protests.

The death of so much potential, so many dreams, and the hollowing out of those left behind in the wake of the AIDS crisis is but a small fraction of the ghosts of our queer ancestors, and our queer selves. In her book, The Apparitional Lesbian, Terry Castle writes, “The lesbian remains a kind of ‘ghost effect’ in the cinema world of modern life: elusive, vaporous, difficult to spot—even when she is there, in plain view, mortal and magnificent, at the center of the screen. Some may deny she exists at all. The lesbian is never with us, it seems, but always somewhere else: in the shadows, in the margins, hidden from history, out of sight, out of mind, a wanderer in the dusk, a lost soul, a tragic mistake, a pale denizen of the night. She is far away and she is dire.” So many queer and trans bodies and identities are intentionally ghosted in our culture, because if they are absent and apparitional, they need not be acknowledged, respected, or given a place within the practiced hegemony.

Homosexuality has long been associated with illness, silence, death, loss, and mourning in our culture. Long before the existence of AIDS, homophobic Western society began constructing homosexuality as an illness to provide themselves with ammunition with which to delegitimize gay rights. This lays the framework for a dominant culture to medicalize, treat, and “cure” homosexuality—or in other words, police, contain, and remove it. In almost the same fashion, our sensation-seeking Western culture has attempted to sterilize and clinicalize death. We put it behind closed doors, we refuse to speak of it unless we must. Our doctors are trained to treat up until the bitter end, seeing death as a failure and not as an essential part of life. Just like death, we cannot be medicalized, ignored, or contained, we exist—in all our raw, messy, beautiful queer glory, whether society acknowledges our presence or not. Like the melancholy souls in our favorite spooky stories, the ghosts of gays past will not be ignored, sooner or later a spectral hand is going to spin society around to face what it has done. It is our duty, our obligation to listen to the stories of the dead, they are watching and waiting to finally be seen.