Almost every history museum across the globe has a mummy room. No matter the size, they often feature the same ostentatious golden trimmings and royal blue accents adorning faux plaster walls heavily laden with nonsensical hieroglyphics. Wide-eyed school children marvel at the glitz and glamor, gilded statues, chairs, and tables preceding more precious artifacts, such as bejeweled funerary masks and meticulously carved canopic jars. But the main event—what they are all here to see—lies just beyond. In a dramatically lit room—sometimes even with their own personal soundtrack—an ancient wonder is waiting in repose. Peeking through their fingers, anxious children catch their first glimpse of the mummy, dusty and dry, as they lie exposed to the prying eyes of any who dares to look. This up close and personal reminder that one day everyone will die may leave some viewers pensive. But are these gawking museum-goers asking the right questions? As patrons shuffle out through a gift shop packed with plastic blue and gold trinkets, pondering what will be inscribed on their future tombstones, mummies will find themselves alone in a strange land thousands of years and miles away from home. With personal mortality in mind, are larger issues of racism, imperialism, and scientific ethics even given a second thought? In museums all over the world people pay to see mummies and other trafficked human remains on display that found their way there through dubious channels at best—and at worst—outright illegal and unethical means. By stealing human bodies which were carefully prepared in accordance with their native religious and cultural practices, Western academia has robbed indigenous peoples worldwide of a vital part of their cultural identity.

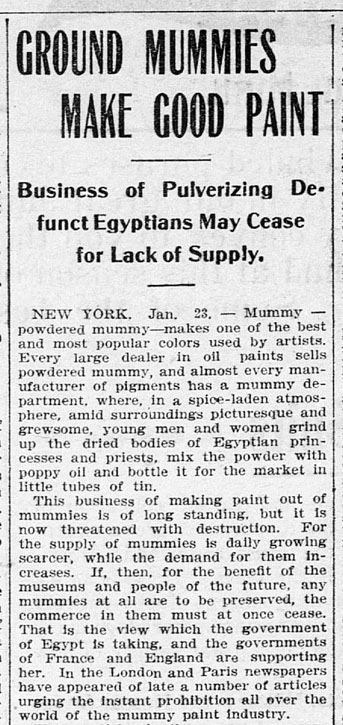

Egyptomania took the world by storm at the beginning of the nineteenth century, due largely to French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte’s Egyptian campaign, during which the many scholars and scientists who accompanied him documented the ancient culture’s monuments and unearthed the famous Rosetta Stone. Renewed Western interest in Egypt exploded shortly thereafter, when in 1822, scholar Jean-François Champollion translated the hieroglyphics on the stone and founded the scientific field of Egyptology. Both Europeans and Americans found themselves clamoring to own a piece of the mysterious ancient culture, the most prestigious symbol of which was the mummy. Europeans had been importing mummies since the thirteenth century, though mostly for medicinal purposes—the ancient bodies were ground into a paste called “Mummia” or dissolved into tinctures consumed to combat every manner of malady from toothaches to dysentery. In the sixteenth century mummy usage shifted from medicinal to artistic when it became the main ingredient for an otherwise unobtainable shade of oil paint unabashedly named “Mummy Brown” and graced the paintings of novice artists and Pre-Raphaelite masters alike. These practices helped cement the foundation of the pervasive belief that the remains of people from other cultures are not due the same respect given to our own culture’s dead but are instead something to be consumed and commoditized.

The most grievous exploitation of ancient Egyptian remains would become one of the most popular social events of the Victorian era—the mummy unwrapping party. This pastime would enrapture Britain, and enterprising would-be antiquarians put on this macabre display to sold-out venues for immense sums. One of these self-styled authorities, Thomas “Mummy” Pettigrew, not only profited wildly from the shocking spectacle of disrobing ancient corpses but used the opportunity to champion the racist pseudo-science of phrenology, measuring mummy skulls to ‘prove’ that they were in fact Caucasians, and not Africans. This insidious and farcical ‘science’ has been debunked numerous times throughout history, but at the time it was widely accepted, as it furthered the idea that such a culturally advanced, historically important, and influential society could only have been accomplished by people who looked just like them. The proliferation of this view only served to reinforce the European attitude of entitlement to the remains of ancient Egyptians, and Pettigrew’s popularity saw him become a founding member of the British Archeological Society. Though the Ancient Egyptian mummy displays in modern museums are a far cry from the exploitation such corpses used to endure just a short one hundred and fifty years ago, they are still raking in profits from the ill-gotten goods of conquest, colonialism, and a legacy of Eurocentric imperialism.

Not about to be outdone by British exploitation of antiquity, Americans zealously formed their own expeditions and the young nation saw many companies of archeologists launched into Egypt around the turn of the century. Starting in 1905, the Hearst Expedition, based out of the University of California, and later Harvard University in Boston, spent a total of thirty-nine years and today’s equivalent of thirty-one million dollars working its way up the Nile Valley. Profiting from the spectacle of mummy display was nothing new to Americans though, as one unlucky mummy had been on tour several times in the states as a fundraising gimmick for the Harvard Medical School hospital. Padihershef, whose body and sarcophagus were stolen from his burial site in Thebes, was gifted to the city of Boston and the young medical school by Dutch merchant Jacob Van Lennep in 1823. Curious Americans lined up to see the touring mummy for the price of twenty-five cents a person, and the unwitting Padihershef raised twelve-hundred dollars for the hospital, a hefty sum of almost $28,000 today. The two-thousand-two-hundred-year-old mummy is still on display to the public in Harvard Medical School’s famous Ether Dome, the surgical amphitheater where the first demonstration of surgery under anesthesia was performed in 1846. There he continues to draw visitors and promote the school with public viewings and for a time, his own Facebook page. At any point in the last two-hundred years the administrators of the Harvard Medical School could have reexamined the ethics of owning, displaying, and profiting from the body of someone who certainly did not consent to being exhumed from his grave and shipped to the other side of the world to be gawked at by spectators. But there he remains, a silent observer to countless surgeries and lectures, himself the subject of both several times over the course of his captivity.

Recently there has been a marked improvement in the way many displays of human remains in museums are framed, with carefully crafted language designed to provoke thoughtful inquiry about the context of the displays. One such display of tsantsas, the carefully preserved human heads crafted by the Shuar and Achuar peoples of the Peruvian and Ecuadorian rainforest commonly known as “shrunken heads,” resides in the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University in England. Tsantsas, like Egyptian mummies, have long been a coveted prize in the collections of colonial-era antiquarians who obtained them through practices that were exploitative or illegal even in their own time. In 2019, the staff at Pitt Rivers enacted a much-debated reframing of the human skulls and tsantsas being displayed in vitrines alongside associated ritual objects from their respective cultures. Obscuring the contents of these cases are signs posing questions to would be observers such as “How would you feel if the remains of your family members were taken and put on public display?” Another asks visitors “How would you feel walking into the Museum and seeing, without warning, the skull of a grandparent looking back at you from the displays?”

Such questions encourage the overwhelmingly white Oxford Museum goers to think themselves into perspectives that descendants of indigenous peoples whose ancestral remains are on display have been voicing for many years. Former museum curator and professor of history Christina Riggs points out that as well-intentioned as these prompts are, they lack nuance, and “they imply that ideas about death and the dead are universal, that all bodies are equal, and that the values of Oxford museum-goers outweigh the values of living descendants or, for that matter, of those people in the past who were responsible for making tsantsas or embalming ancient Egyptians.” While this is a start to the critically important global conversation about the possession and display of one culture’s human remains by another culture, it is not enough. The continued impact of these displays sensationalizes and misrepresents cultural practices like tsantsa making instead of fostering cross-cultural understanding by working with the still living communities and cultures that they represent.

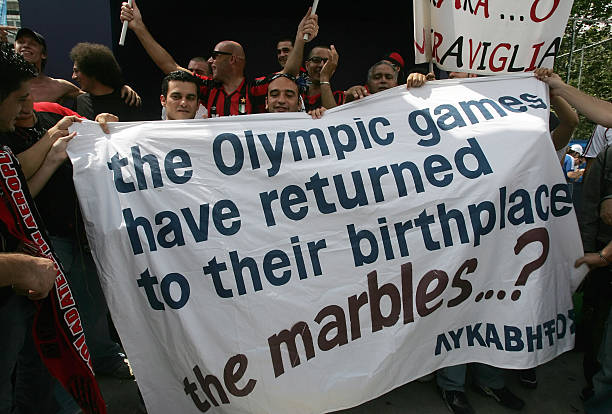

A common defense against repatriation of native remains is that museums act as the guardians of history—the lofty custodians and valiant conservers of humanity’s collective cultural and natural treasures. While this may seem like a noble charge, what this argument is essentially saying is that the descendants of the cultures these pilfered artifacts and remains originally belonged to cannot be entrusted with their own cultural heritage. Cultures still living, like Ethiopians, Native Americans, Greeks, or Indians, whose artworks, artifacts, and human remains have long been subject to cultural looting and vandalism, are perfectly capable of being the caretakers of their own legacy.

Even in the depths of riots surrounding the 2008 economic crisis, the Greek public was careful not to vent their fury on historical sites, instead attacking ATMs and banks—the arteries of the capitalist system which brought about the collapse. Despite the multitudes of stolen artwork and artifacts of Greek origin bringing in millions of dollars to foreign museums across the globe, one in five Greeks fell below the poverty line at the time of the country’s imminent financial doom, which prompted the government to enact a series of austerity measures that wiped out almost every right won by workers over the previous thirty years. Grecian artifacts and artworks abroad, like the Elgin Marbles, which were illegally removed by agents of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin 200 years ago and now reside in the British Museum, could have been rented from the Greek government for continued display to help bolster their economy and avoid such economic disaster. The theft of these and other artifacts from ancient, yet still living cultures by imperialistic foreign powers is part of the legacy of Western exploitation that pushes conquered nations to the brink and then touts this self-fulfilling prophecy as proof that they are incapable of safeguarding their own history.

A more serious problem than the financial implications of retaining artworks, artifacts, and human remains in foreign museums is that the thousands of articles collected in these museums are not accompanied by their original history. They are collected, organized, given tags, and identified by Europeans, who have, and often still do, perpetuate stereotypical narratives about Africans and other colonized peoples. When given the power to select, name, and instill meaning into these bodies and artifacts, Western museums are making themselves the authors of another culture’s history. Senior Lecturer on African Studies at Curtin University in Perth, Australia, and native Ethiopian, Dr. Yirga Gelaw Woldeyes is one of many voices in the call for repatriation of human remains and cultural artifacts to Africa and other indigenous cultures. When speaking about the theft of African culture he brings to light the legacy of racism that solidified European colonizers as the stewards of African history, and their continued misrepresentation of Africans via museum displays:

“They don’t express Africa’s history or culture, or offer any means of “cultural exchange or mutual understanding”, as the International Council of Museums suggests. They are parts of the legacy of European men who travelled to distant lands and brought items of interest that fascinated their audience in what was then known as the cabinet of curiosity, a popular way of representing unknown places and lives. The cabinets of curiosity evolved into modern museums. In several western ethnological museums where colonial items are still kept, Africans continue to be depicted as warrior tribes, with superstitious beliefs, and homogenous and unchanging cultures. Even when museums attempt to offer an insight into the original purpose or meaning of certain artefacts, they inevitably come from a European perspective.”

Repatriation is the only path to addressing the historical injustices perpetrated by the collectors and museums of colonizing nations on indigenous cultures across the globe. It is crucial to restore the agency of native peoples as the authors and keepers of their own history because the dispossession of their cultural artifacts has very real consequences. Peoples whose religious relics, cultural artifacts, and ancestral remains have been stolen from them and rebranded to fit within a Eurocentric historical narrative are also being robbed of a vital, though intangible, inheritance as well—their collective knowledge, history, religion, and philosophy—in other words, their cultural identity.

‘Which case has the shrunken heads?’

Costs of repatriation are often decried as a major hindrance to museums, even by those who may want to work with native cultures to return artifacts or repatriate remains. However, putting a price limit on restorative justice is not only wrong, but it fails to address the profits these museums have already made by displaying these remains to begin with. Human remains are often the biggest attraction at many museums, as a former director of the Pitt Rivers Museum told celebrated art journalist Martin Bailey, “The tsantsas are the museum’s most famed objects… the most commonly asked question by visitors is: ‘Which case has the shrunken heads?’” The celebrated fundraising tour of Padihershef is another example of the way museums, and often their associated universities, have profited from unethically obtained artifacts and human remains. Many of these remains, like Padihershef, have been on continuous display for hundreds of years, certainly the amount of money their continued presence has contributed to these institutions can afford them a return ticket home and a respectful resting place.

Scientists and historians are quick to point out the many potential benefits of the continued possession and study of human remains contained in museums to the collective knowledge of the academic community, and this reasoning is a popular argument against repatriation. While their continued study could yield new and important scientific revelations, the champions of this argument are not considering the ethics of using science obtained via unethical means. The question of provenance on displays of human remains throughout many museums is often obscured, omitted, or oversimplified, and, with disconcerting frequency, falsified.

One example of this unethical procurement of indigenous remains is the case of the Haida First Nations people of British Columbia who, in the 1990’s, discovered that the remains of almost five-hundred of their ancestors had been removed from grave-sites in old Haida villages and placed in various museums. These villages had been abandoned in the nineteenth century following a small-pox epidemic that killed ninety percent of the Haida population. There is something especially sinister about the descendants of European colonists exhuming remains of the native people their forebearers perpetuated genocide against to put them proudly on display. It took a committee formed of several modern Haida communities working for six years to locate and return the remains from collections in Canada and the United States. According to the American Medical Association’s Code of Medical Ethics,

“Research that violates the fundamental principle of respect for persons and basic standards of human dignity, such as Nazi experiments during World War II or from the US Public Health Service Tuskegee Syphilis Study, is unethical and of questionable scientific value. Data obtained from such cruel and inhumane experiments should virtually never be published. If data from unethical experiments can be replaced by data from ethically sound research and achieve the same ends, then such must be done.”

The data gathered from studying stolen indigenous remains violates this important principle of scientific ethics, it was unethically obtained, therefore its value is nullified. If there are significant studies to be done on these remains, the ethical way to proceed is to first repatriate the remains to their respective culture and then seek official permission to work together on future studies.

The benefits of human remains as well as cultural artifact repatriation are just beginning to be seen, in cases such as the Haida people mentioned above, the homecoming of their ancestor’s remains instilled a renewed cultural interest in younger generations of the tribe. Those who participated in the recovery and reburial of their ancestors sought out the advice of elder community members and historical documents to give the remains a proper burial in keeping with the religion and traditions of their own time. This caused them to relearn ancient arts and techniques, like bentwood box-making, weaving of cedar bark mats, and decorative beading methods not practiced for decades. All of this cultural learning sparked a fire of communal pride and stimulated the development of new songs and dances to celebrate the return of their ancestors.

We can tell our own story. That’s my point.

– Vince Collison

The Haida built a new museum and cultural center where feasts and ceremonies will be held to keep the connection to their culture and history alive. Another example is the return of sixteen mummified heads of Māori peoples from museums across France to New Zealand in 2010. In traditional Māori practice, the tattooed heads of one’s ancestors were preserved and kept as totems to honor their spirits, but macabre colonial-era obsession with them led to extensive trade similar to that of Egyptian mummies and Ecuadorian tsantsas. On the repatriation of these sixteen heads to representatives of the Māori people, French cultural minster Frederic Mitterand said, “You do not build a culture on trafficking, you build a culture on respect and on exchange.” Though it is worth noting that just a few years before this decision, his ministry blocked a museum based in Rouen’s independent offer to return a Māori head in its possession as an act of atonement, perhaps out of fear that it might lead to further emptying of other unknown skeletons in French academia’s collective closet.

The path of restorative justice is a long and arduous one, with many deep-seeded racial issues to be unpacked and dismantled. But it is a vital process for the healing of indigenous communities worldwide, and the return of their ancestral remains should be the first step of many performed by colonial powers towards building newer and healthier relationships. Kalpana Nand, the Education Officer of the Fiji Museum, states: “Culture is a living, dynamic, ever-changing and yet ever-constant thing – it is a story, a song, a dance performance, never a ‘dead thing’ to be represented in the form of an artifact to be looked at through glass.” By reducing cultures down to a handful of items jealously guarded on dusty museum shelves, Western museums are doing a grave disservice to the people that are descended from and still living in those cultures. Difference is a teacher, and in order to truly learn from and appreciate the beauty of cultures both ancient and modern, museums and other academic institutions must let their stories be told by the people who lived them.